A pastor as toad conservationist

With God’s help for the toads

How on earth did a pastor and teacher go to the frogs? Actually, he had wanted to become a biologist. Because of his passion for animals. It must have been in 1974 when five-year-old Ole was waiting at the dentist’s office and, tormented by boredom, picked up one of the picture books on display. It was about amphibians, the development from egg to tadpole to the finished amphibian, about the biggest and the smallest frog in the world. The boy was immediately enthusiastic, it was a love at first sight that would not let him go. Perhaps it was God’s providence. In the end, he studied Protestant theology, but as an enthusiastic nature photographer, he continued to devote his free time to frogs. An educational path from pastor to toad protector!

From nature photographer to amphibian breeder

Schon als Kind schleppte Ole allerlei Getier nach Hause, fasziniert saß er vor dem Fernseher, wenn Sielmann und Professor Grzimek die Zuschauer mitnahmen auf ihre Expeditionen ins Reich der wilden Tiere, und die Schülerzeitschrift „Tierfreund“ ließ ihn staunend die Bilder renommierter Fotografen betrachten – das weckte den Wunsch, selbst Tiere zu fotografieren. Mit dem ersten durch Schülerjobs selbst verdienten Geld kaufte er sich eine gute Kamera, und los ging´s! Doch viele Amphibien ließen sich in allen ihren Verhaltensweisen nur schwer in freier Natur dokumentieren. So kam Ole zur Terraristik.

Ole's favorite photo subjects

The Western Ghats in India are a hotspot of amphibian diversity. Here, amateur nature photographer Ole Dost finds plenty of photo motifs during his excursions, such as the Asian black-spined toad (Duttaphryne melanostictus), which is widespread in South Asia. | Ole Dost

Ghaticxalus asterops is the most strikingly colored member of its small frog genus, found only in the Western Ghats. | Ole Dost

Among the least known amphibians are the subterranean caecilians. Only during heavy rainfall does Ichtyophis kodaguensis dare to come to the surface. | Ole Dost

Die Gattung Indosylvirana kommt fast ausschließlich in den Western Ghats vor. Indosylvirana sreeni lebt am Rand von Gewässern und ist immer bereit, mit einem beherzten Sprung ins rettende Nass einzutauchen. | Ole Dost

For humans, the more than 20 species of the genus Minervarya are hardly distinguishable. And yet each has its own call, and the females of Minervarya mudduraja know exactly that they are expected by this male. | Ole Dost

Wie in allen tropischen Regionen teilt man auch in den Western Ghats seine Unterkunft häufig mit einem sympathischen Badezimmerfrosch. Hier hat Polypedates maculatus sich dieser Rolle angenommen. | Ole Dost

Although the shrub frog Polypedates pseudocruciger belongs to a genus that is widespread and species-rich in South Asia, it is found here exclusively in the Western Ghats. | Ole Dost

In an altitude range between 1,500 and 2,600 meters the characteristic shola forests are growing, evergreen tree groves embedded in grassland. Unfortunately, they have been largely deforested, and with them the Raochrestes chlorosomma, which only lives here, is threatening to disappear. | Ole Dost

Besonders hübsch ist die zweifarbig rot und blau leuchtende Iris von Especially pretty is the bicolor red and blue iris of Raorchestes glandulosus. | Ole Dost

Coffee plants are ideal calling grounds for the reproductively active males of Raochestes jayarami | Ole Dost

The somewhat bulbous Uperodon triangularis lays its eggs in water-filled tree cavities of upland forests. | Ole Dost

It is worth looking deep into the eyes of Raorchestes luteolus, which are usually yellowish orange at mating time - for they are adorned with a fine blue ring. | Ole Dost

Raorchestes sushili also lives in the endangered shola forests. | Ole Dost

The most colorful frog of the Westghats is probably Rhacophorus lateralis. If you get funny with him, he can change his color to a dirty brown. | Ole Dost

The flying frog Rhacophorus malabaricus can cover a distance of over ten meters with its gliding jump | Ole Dost

The call of the wild

In the terrarium, Ole brought nature home to photograph, but photography always brought him into the wild. After years of photographing native species, he was lured by the biodiversity of the rainforests. Looking for a conveniently accessible destination, he came across the little-known Western Ghats mountain range in southern India – a global amphibian hotspot. He was enthralled by the region’s richness of species and individuals, and returned here again and again for new photo safaris.

From a racing bike riding pastor to a toad

With the racing bike to the toad

Besides photography, Ole also indulges in road cycling. His home in the Black Forest offers plenty of beautiful routes with decent climbs. He participated in cycling marathons all over Europe. It was also a bike race that took him to Mallorca in the Serra de Tramuntana. Later, he read in a journal that in the ravines there a living fossil has survived to this day: the Mallorca midwife toad. It is critically endangered, but its population has been stabilized through a dedicated zoo breeding program. When Citizen Conservation offered the opportunity for private owners to join this conservation project, Ole was immediately on board.

Enthusiastic about nature

Ole has not only been able to get his own two children excited about amphibians; the biology teachers at his school have also had the clerical colleague design an amphibian course. With great success: “Even the most behaviorally challenged students were captivated by the live frogs on display,” he reports. “Our youth are not supposed to be enthusiastic about nature? Nonsense! What’s crucial here is the personal experience.” That’s another reason he’s a convinced participant in Citizen Conservation. “There I can kill two birds with one stone: commitment to species conservation and arouse enthusiasm in others for these endangered animals!”

Biannual report 1 / 2021 – status update

Protecting species - Animal inventory November 1st, 2021

A second six months under the Corona crisis – a species conservation program is suffering from lockdowns, too. International projects lie idle, zoos are closed, transport and transfer options are limited. When mobility reduction is the order of the day, even frogs have to keep still. As a result, many projects could only be carried out under reservations. Accordingly, progress has been slow since the last half-yearly review.

When problems confirm the general direction

Working with live animals is different from working with machines. It is alive! – with all the problems and setbacks that go with it. This is where CC’s approach proves itself. The continuous veterinary screening costs are high, but the approach has uncovered several outbreaks of the dreaded frog fungus Bd at once, so that they could ultimately be contained.

Steadiness through coordination

Failures can always occur when working with live animals. Without reporting and coordination, populations in human care quickly die out, as has often happened in the past. In the case of lemur leaf frogs, which are critically endangered in the wild, CC can now take targeted countermeasures and bring new breeding groups together before it is too late. We hope that this will also succeed with the demonic poison frogs. So far, there are not enough animals to build a breeding program. The five specimens kept for CC in 2018 unfortunately died earlier this year.

Amphibian nurseries

Earlier this year, the golden poison frog came to CC as a new species. This critically endangered frog species is found only in a small area in southwestern Colombia. Also, despite Corona, some of the CC animals came directly from Colombia – from an amphibian breeding station certified by the Colombian state. A first genetic screening shows that they are the same species as CC animals from German breeding stock. Hopefully, this lays the foundation for sustainable conservation breeding.

A golden new species

In the case of the critically endangered lake Pátzcuaro salamanders, not only could a considerable number of the fragile larvae be raised to a “safer” age, but there were also new offspring. And in the case of the endangered Vietnamese crocodile newt, which was successfully bred for the first time three years ago at Cologne Zoo, CC was immediately able to breed again. And in the case of the Majorcan midwife toads, new tadpoles are swimming through CC’s aquariums, despite the fungus problem.

Stock overview May 2023

(You can scroll horizontally in the table.)

| Wiss. Name | Dt. Name | Bestand Tiere (m/w/u) | Anzahl Haltungen | Todesfälle 05/23 – 10/23 (m/w/u) | Abgabe extern 05/23 – 10/23 | Zugänge Nachzucht 05/23 – 10/23 | Zugänge extern 05/23 – 10/23 | Ziel (Tiere, Halter) | Status* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amphibien | |||||||||

| Agalychnis lemur | Lemur-Laubfrosch | 51 (13/10/28) | 8 | 9 (1/1/7) | 0 | 16 | 0 | 225, 40 | 21 % |

| Alytes muletensis | Mallorca-Geburtshelferkröte | 701 (12/13/676) | 37 | 26 (0/0/26) | 0 | 401 | 0 | 425, 53 | 85 % |

| Ambystoma andersoni | Andersons Querzahnmolch | 69 (20/21/28) | 8 | 11 (5/3/3) | 0 | 8 | 0 | 225,40 | 25 % |

| Ambystoma dumerilii | Pátzcuaro-Querzahnmolch | 206 (60/46/100) | 27 | 62 (0/0/62) | 11 | 41 | 0 | 225, 40 | 80 % |

| Atelopus balios | Rio-Pescado-Harlekinkröte | 29 (9/9/11) | 4 | 1 (0/1/0) | 0 | 0 | 30 | ** | ** |

| Bombina orientalis | Chinesische Rotbauchunke | 243 (37/22/184) | 21 | 13 (0/0/13) | 0 | 50 | 13 | 225, 60 | 68 % |

| Ecnomiohyla valancifer | San-Martín-Fransenbeinlaubfrosch | 22 (0/0/22) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22 | ** | ** |

| Epipedobates tricolor | Dreistreifen-Blattsteiger | 45 (0/0/45) | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 45 | ** | ** |

| Gastrotheca lojana | Loja-Beutelfrosch | 12 (0/0/12) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | ** | ** |

| Ingerophrynus galeatus | Knochenkopfkröte | 40 (12/11/17) | 6 | 11 (6/0/5) | 0 | 0 | 5 | 225, 40 | 16 % |

| Minyobates steyermarki | Tafelberg-Baumsteiger | 26 (5/4/17) | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 110, 20 | 24 % |

| Phyllobates terribilis | Schrecklicher Blattsteiger | 33 (9/5/19) | 4 | 6 (2/2/2) | 0 | 13 | 9 | 225, 70 | 10 % |

| Salamandra sal. almanzoris | Almanzor-Feuersalamander | 24 (17/7/0) | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 185, 30 | 18 % |

| Salamandra salamandra (D) | Feuersalamander | 152 (19/12/121) | 16 | 3 (0/2/1) | 3 | 0 | 72 | 330, 90 | 32 % |

| Telmatobius culeus | Titicaca-Riesenfrosch | 41 (12/14/15) | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 225,45 | 17 % |

| Tylototriton vietnamensis | Vietnamesischer Krokodilmolch | 200 (39/33/138) | 28 | 36 (6/9/21) | 0 | 5 | 38 | 185, 30 | 97 % |

| Tylototriton ziegleri | Zieglers Krokodilmolch | 24 (7/3/14) | 6 | 4 (3/1/0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 185,30 | 16 % |

| Fische | |||||||||

| Bedotia madagascariensis | Madagaskar-Ährenfisch | 144 (24/20/100) | 10 | 33 (9/6/18) | 0 | 56 | 13 | 192, 16 | 69 % |

| Cyprinodon veronicae | Charco-Azul-Wüstenkärpfling | 16 (6/10/0) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | ** | ** |

| Limia islai< | Tigerkärpfling | 49 (5/5/39) | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 49 | ** | ** |

| Parosphromenus bintan | Bintan Prachtgurami | 8 (4/4/0) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | ** | ** |

| Ptychochromis insolitus | Mangarahara-Buntbarsch | 452 (15/18/419) | 12 | 37 (8/8/21) | 10 | 222 | 0 | 192, 16 | 88 % |

| Ptychochromis loisellei | Loiselles Buntbarsch | 216 (18/18/180) | 7 | 46 (7/1/38) | 0 | 65 | 0 | 160, 16 | 72 % |

| Ptychochromis oligacanthus | Nosy-Be-Buntbarsch | 1096 (8/9/1079) | 4 | 10 (3/2/5) | 0 | 1000 | 0 | 192,16 | 63 % |

| Reptilien | |||||||||

| Cuora cyclornata | Vietnamesische Dreistreifen-Scharnierschildkröte | 1 (1/0/0) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ** | ** |

m: male, w: female, u: undetermined sex

* Status = mean value of the percentage of the target number of keepers already achieved and the target number of animals

** To be determined.

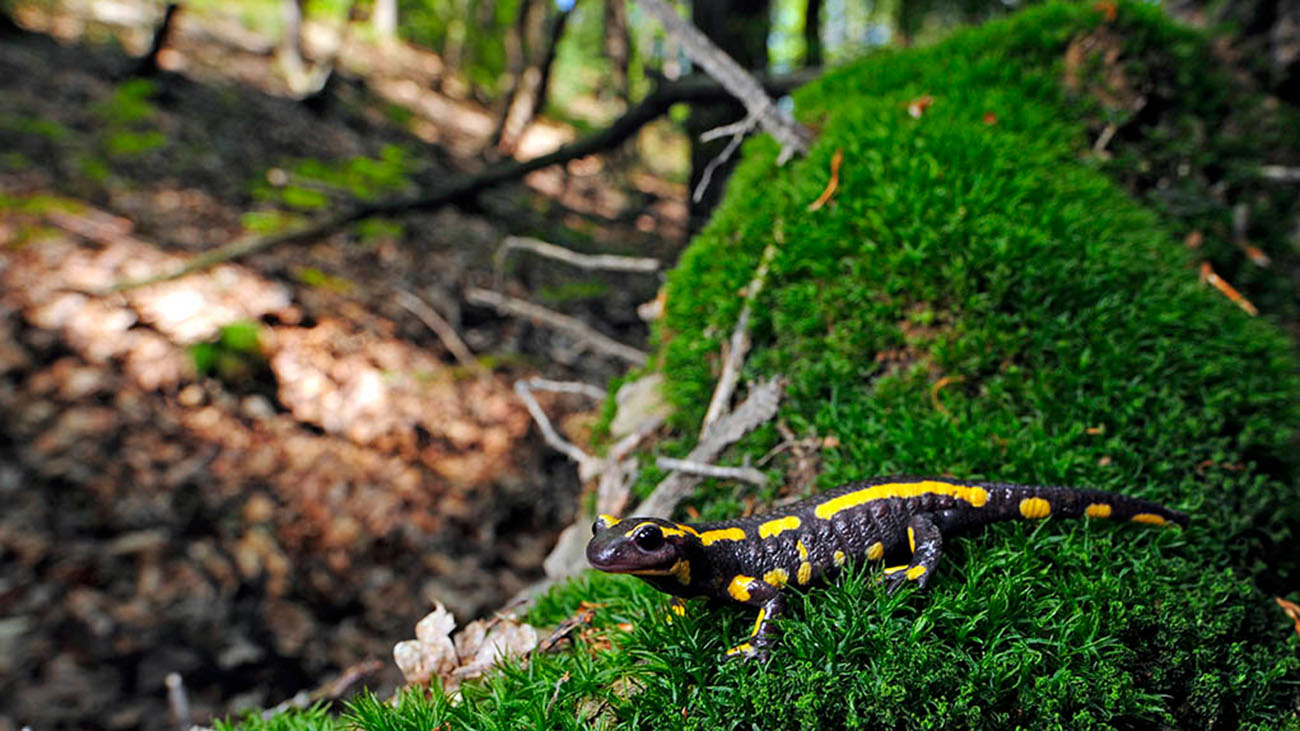

Death in the forest - our fire salamander documentary

The salamander killer is on the loose – and what we can do about it

Overshadowed by the Corona pandemic, a tragedy is also happening in our native hardwood forests. CC produced this fire salamander movie that shows how an introduced fungal disease is killing local fire salamanders that come in contact with it. Discovered about a decade ago, the disease initially spread “on foot” in the tri-border region of Germany – Holland – Belgium. But now it occurred, what scientists feared for a long time: The fungus has jumped. Initial outbreaks in Bavaria in the spring of 2020 mark a new phase of this epidemic, because they mean that potentially all fire salamander populations are at risk, and drastically so – because unlike Covid-19 in humans, mortality in fire salamanders in the case of Bsal is one hundred percent. An infected salamander will die if left untreated.

The jump of the fungus over 500 kilometers is an alarm signal: There are no longer any salamander populations that can be called safe.

Frogs & Friends cameraman Leendert de Jong documents the work of biologist Carolin Dittrich in the Steigerwald.

On behalf of CC, she will move fire salamanders that have tested positive for Bsal to the quarantine at Nuremberg Zoo.

Two weeks of heat chamber followed by four months of quarantine is the life-saving verdict of the Nuremberg veterinarians.

The key question: intervene or simply watch?

Knowledge obliges. How should we react to this acute threat to the fire salamander, which, being a German “species of special responsibility“, has highest priority? The dream of an intact nature, which is best left alone, would mean to watch the eradication of all fire salamanders inactively. The fungus is spread not only by human boots, but also by ducks’ feet and newts’ legs, so even locking people out would not help. What remains, then, is courageous intervention. Accepting responsibility always means the willingness to take risks. We know that Bsal can be cured: we have to give it our best shot. Only in human care can salamanders be saved from infested populations. So we have to do it, even if we cannot know today how and when the way back to the wild will open up.

The good thing about documentaries: no need to intervene, you can simply watch.

Author Susann Knakowske accompanied scientists, conservationists and animal owners on film for over a year. It wasn’t planned, it just turned out that way. Because neither Corona nor the Bsal jump to Bavaria were on the filming schedule when we began preparations for a fire salamander documentary at the end of 2019. And this story is far from over. But the first film is ready and gives an overview of the state of affairs regarding salamander eaters in spring 2021.

Biannual report 2 / 2020 - status update

Protecting species - Animal inventory November 1st, 2020

Citizen Conservation is picking up speed. The founding year 2018 was mainly characterized by preparations and therefore largely theoretical, but in 2019, the first animals already moved in with participants of the conservation breeding program. And, looking back at 2020, you can see: It works! Not only did some animals already reach sexual maturity, but they’ve even had offspring. In addition, some already sexually mature animals that we adopted into the program promptly reproduced under the apparently very favorable conditions created by our breeders.

Amphibian blessing

We are very excited about the 245 little salamanders, toads, and frogs from four different species that saw the light of day (or rather the light of their breeders’ terrariums) as original Citizen Conservation animals. Lemur Leaf Frogs, Lake Patzcuaro Salamanders, Majorcan Midwife Toads, and Vietnamese Crocodile Newts – all species that are endangered or even on the verge of extinction in the wild but are frolicking in the care of our breeders. A good deal of their offspring has already been passed on to new breeders. We’re growing!

Paralyzed by the virus

Originally, we had planned a significant increase in the number of species in CC for 2020. But a virus was blocking our path. Two expeditions to catch breeding animals in Africa were harshly stopped. Planned imports from South America failed due to new restrictions, a lack of flights, and thinned out personnel on both sides of the Atlantic. But we are keeping track of our goals, and hope to be able to carry out our already well-prepared projects in 2021 and 2022.

New Species

2020 did bring some new additions: with the Majorcan Midwife Toad (Alytes muletensis), we are including an endangered European species with a changeable and downright dramatic history. And with the Oriental fire-bellied toads (Bombina orientalis), we are trying out another strategy for species protection. More on this soon, here on the site.

In any case, we are picking up pace, and we are excited to see what 2021 will bring!

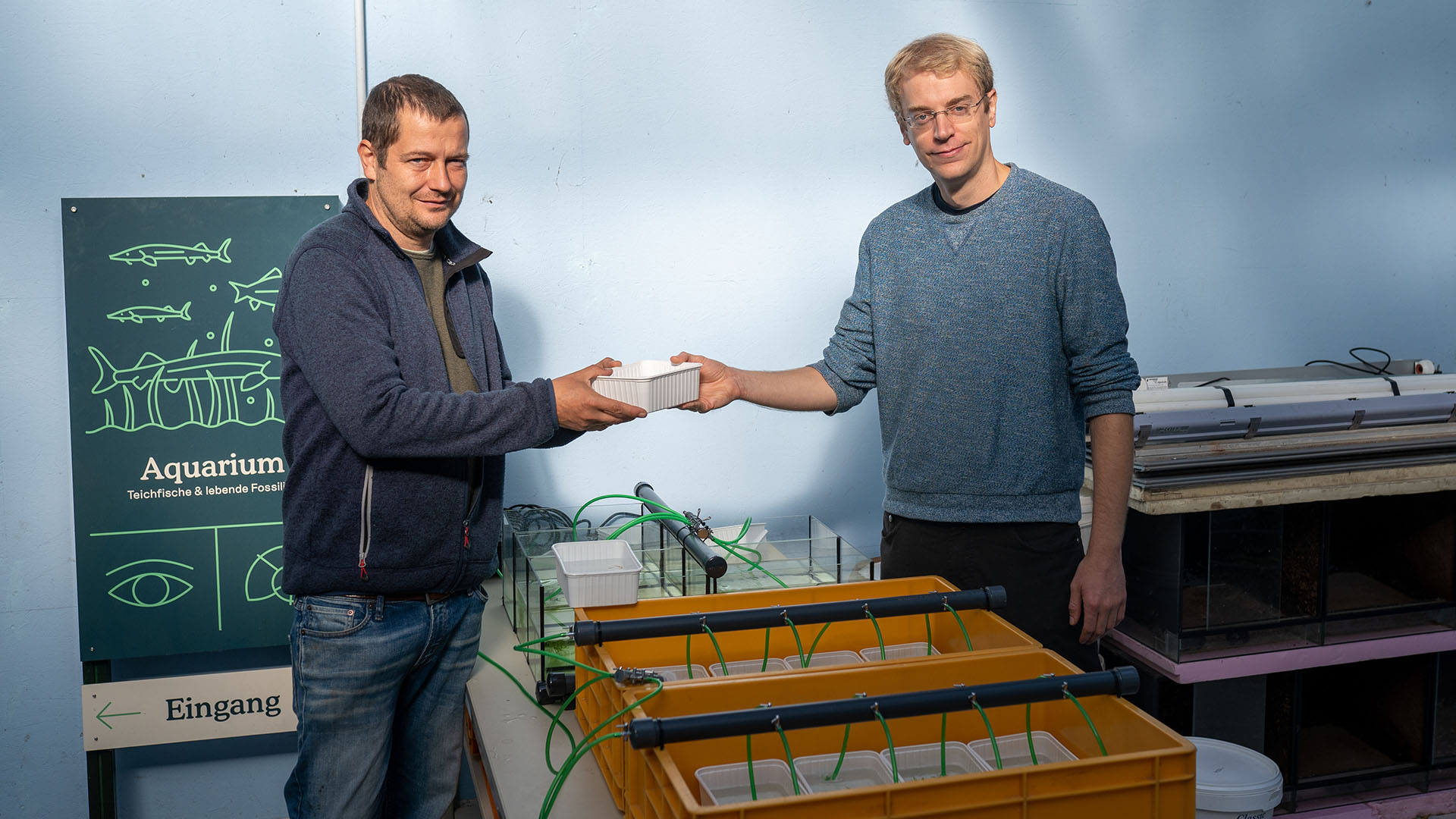

Cooperation between private and institutional breeders: David Kupitz hands over CC offspring of the Lake Patzcuaro Salamander that he bred to Holger Kraus from NaturaGart Ibbenbüren, a show facility with zoo permits for everything to do with garden ponds and freshwater aquariums.

© NaturaGart Ibbenbüren

Stock overview May 2023

(You can scroll horizontally in the table.)

| Wiss. Name | Dt. Name | Bestand Tiere (m/w/u) | Anzahl Haltungen | Todesfälle 05/23 – 10/23 (m/w/u) | Abgabe extern 05/23 – 10/23 | Zugänge Nachzucht 05/23 – 10/23 | Zugänge extern 05/23 – 10/23 | Ziel (Tiere, Halter) | Status* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amphibien | |||||||||

| Agalychnis lemur | Lemur-Laubfrosch | 51 (13/10/28) | 8 | 9 (1/1/7) | 0 | 16 | 0 | 225, 40 | 21 % |

| Alytes muletensis | Mallorca-Geburtshelferkröte | 701 (12/13/676) | 37 | 26 (0/0/26) | 0 | 401 | 0 | 425, 53 | 85 % |

| Ambystoma andersoni | Andersons Querzahnmolch | 69 (20/21/28) | 8 | 11 (5/3/3) | 0 | 8 | 0 | 225,40 | 25 % |

| Ambystoma dumerilii | Pátzcuaro-Querzahnmolch | 206 (60/46/100) | 27 | 62 (0/0/62) | 11 | 41 | 0 | 225, 40 | 80 % |

| Atelopus balios | Rio-Pescado-Harlekinkröte | 29 (9/9/11) | 4 | 1 (0/1/0) | 0 | 0 | 30 | ** | ** |

| Bombina orientalis | Chinesische Rotbauchunke | 243 (37/22/184) | 21 | 13 (0/0/13) | 0 | 50 | 13 | 225, 60 | 68 % |

| Ecnomiohyla valancifer | San-Martín-Fransenbeinlaubfrosch | 22 (0/0/22) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22 | ** | ** |

| Epipedobates tricolor | Dreistreifen-Blattsteiger | 45 (0/0/45) | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 45 | ** | ** |

| Gastrotheca lojana | Loja-Beutelfrosch | 12 (0/0/12) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | ** | ** |

| Ingerophrynus galeatus | Knochenkopfkröte | 40 (12/11/17) | 6 | 11 (6/0/5) | 0 | 0 | 5 | 225, 40 | 16 % |

| Minyobates steyermarki | Tafelberg-Baumsteiger | 26 (5/4/17) | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 110, 20 | 24 % |

| Phyllobates terribilis | Schrecklicher Blattsteiger | 33 (9/5/19) | 4 | 6 (2/2/2) | 0 | 13 | 9 | 225, 70 | 10 % |

| Salamandra sal. almanzoris | Almanzor-Feuersalamander | 24 (17/7/0) | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 185, 30 | 18 % |

| Salamandra salamandra (D) | Feuersalamander | 152 (19/12/121) | 16 | 3 (0/2/1) | 3 | 0 | 72 | 330, 90 | 32 % |

| Telmatobius culeus | Titicaca-Riesenfrosch | 41 (12/14/15) | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 225,45 | 17 % |

| Tylototriton vietnamensis | Vietnamesischer Krokodilmolch | 200 (39/33/138) | 28 | 36 (6/9/21) | 0 | 5 | 38 | 185, 30 | 97 % |

| Tylototriton ziegleri | Zieglers Krokodilmolch | 24 (7/3/14) | 6 | 4 (3/1/0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 185,30 | 16 % |

| Fische | |||||||||

| Bedotia madagascariensis | Madagaskar-Ährenfisch | 144 (24/20/100) | 10 | 33 (9/6/18) | 0 | 56 | 13 | 192, 16 | 69 % |

| Cyprinodon veronicae | Charco-Azul-Wüstenkärpfling | 16 (6/10/0) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | ** | ** |

| Limia islai< | Tigerkärpfling | 49 (5/5/39) | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 49 | ** | ** |

| Parosphromenus bintan | Bintan Prachtgurami | 8 (4/4/0) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | ** | ** |

| Ptychochromis insolitus | Mangarahara-Buntbarsch | 452 (15/18/419) | 12 | 37 (8/8/21) | 10 | 222 | 0 | 192, 16 | 88 % |

| Ptychochromis loisellei | Loiselles Buntbarsch | 216 (18/18/180) | 7 | 46 (7/1/38) | 0 | 65 | 0 | 160, 16 | 72 % |

| Ptychochromis oligacanthus | Nosy-Be-Buntbarsch | 1096 (8/9/1079) | 4 | 10 (3/2/5) | 0 | 1000 | 0 | 192,16 | 63 % |

| Reptilien | |||||||||

| Cuora cyclornata | Vietnamesische Dreistreifen-Scharnierschildkröte | 1 (1/0/0) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ** | ** |

m: male, w: female, u: undetermined sex

* Status = mean value of the percentage of the target number of keepers already achieved and the target number of animals

** To be determined.

Biannual report 1 / 2020 - status update

Conservation protects species – preliminary results 2020

A year and a half ago, we started developing our conservation breeding program using amphibians as an example. This included everything that belongs in a pilot phase: Setting up the organizational structure, the website, the administration. Funding had to be secured, the workforce built up, and of course we had to introduce CC to the public. We started with five “example species”.

In the midst of the pilot phase

We are still in the middle of this pilot phase. But something is happening to the animal population, something very elementary: the animals are getting older and are gradually reaching sexual maturity. So far, we assembled the CC animal population from breeding animals from zoos and private owners who came to our program as adolescents. Depending on the species, it takes a long time before they themselves are old enough to give birth to newborns.

On the brink of adulthood

Our Lake Patzcuaro Salamanders are slowly but surely growing up. Last fall, a female salamander laid a first clutch of eggs in the Münster Zoo, from which two larvae hatched, but unfortunately have not developed yet. Nevertheless: it’s a beginning! Our bony-headed toad breeders are reporting of their first attempts to get into the amplexus – the clasped position the frogs use for mating. We are optimistic that we will be able to show our first breeding successes for these species in 2020.

Patience please

With the Almanzor fire salamanders, it will probably take a year or two until the young animals reach sexual maturity. In contrast, the Demonic poison frogs and the Lemur leaf frog so far have not succeeded in building potential breeding groups. With such rare species, it is sometimes hard to get suitable pilot animals in the first place. But we do have some good news from the Lemur leaf frog: We will soon be able to add a large number of young leaf frogs to the project, so that in 2020/21 we can hope for offspring from these critically endangered frogs.

Jumpstarter

As our sixth and final species, we were able to add the Vietnamese crocodile newt to the CC program. The first ever successful breeding of these rare amphibians took place in the Cologne Zoo the year before. And they did not slow down: As soon as they were moved to a private CC breeder at the turn of the year, they started their reproductive activities. In the meantime, the first larvae are growing up, and we are optimistic that we will be able to show the first own CC offspring of this species in our next biannual figures on November 1, 2020.

Stock overview May 2023

(You can scroll horizontally in the table.)

| Wiss. Name | Dt. Name | Bestand Tiere (m/w/u) | Anzahl Haltungen | Todesfälle 05/23 – 10/23 (m/w/u) | Abgabe extern 05/23 – 10/23 | Zugänge Nachzucht 05/23 – 10/23 | Zugänge extern 05/23 – 10/23 | Ziel (Tiere, Halter) | Status* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amphibien | |||||||||

| Agalychnis lemur | Lemur-Laubfrosch | 51 (13/10/28) | 8 | 9 (1/1/7) | 0 | 16 | 0 | 225, 40 | 21 % |

| Alytes muletensis | Mallorca-Geburtshelferkröte | 701 (12/13/676) | 37 | 26 (0/0/26) | 0 | 401 | 0 | 425, 53 | 85 % |

| Ambystoma andersoni | Andersons Querzahnmolch | 69 (20/21/28) | 8 | 11 (5/3/3) | 0 | 8 | 0 | 225,40 | 25 % |

| Ambystoma dumerilii | Pátzcuaro-Querzahnmolch | 206 (60/46/100) | 27 | 62 (0/0/62) | 11 | 41 | 0 | 225, 40 | 80 % |

| Atelopus balios | Rio-Pescado-Harlekinkröte | 29 (9/9/11) | 4 | 1 (0/1/0) | 0 | 0 | 30 | ** | ** |

| Bombina orientalis | Chinesische Rotbauchunke | 243 (37/22/184) | 21 | 13 (0/0/13) | 0 | 50 | 13 | 225, 60 | 68 % |

| Ecnomiohyla valancifer | San-Martín-Fransenbeinlaubfrosch | 22 (0/0/22) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22 | ** | ** |

| Epipedobates tricolor | Dreistreifen-Blattsteiger | 45 (0/0/45) | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 45 | ** | ** |

| Gastrotheca lojana | Loja-Beutelfrosch | 12 (0/0/12) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | ** | ** |

| Ingerophrynus galeatus | Knochenkopfkröte | 40 (12/11/17) | 6 | 11 (6/0/5) | 0 | 0 | 5 | 225, 40 | 16 % |

| Minyobates steyermarki | Tafelberg-Baumsteiger | 26 (5/4/17) | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 110, 20 | 24 % |

| Phyllobates terribilis | Schrecklicher Blattsteiger | 33 (9/5/19) | 4 | 6 (2/2/2) | 0 | 13 | 9 | 225, 70 | 10 % |

| Salamandra sal. almanzoris | Almanzor-Feuersalamander | 24 (17/7/0) | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 185, 30 | 18 % |

| Salamandra salamandra (D) | Feuersalamander | 152 (19/12/121) | 16 | 3 (0/2/1) | 3 | 0 | 72 | 330, 90 | 32 % |

| Telmatobius culeus | Titicaca-Riesenfrosch | 41 (12/14/15) | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 225,45 | 17 % |

| Tylototriton vietnamensis | Vietnamesischer Krokodilmolch | 200 (39/33/138) | 28 | 36 (6/9/21) | 0 | 5 | 38 | 185, 30 | 97 % |

| Tylototriton ziegleri | Zieglers Krokodilmolch | 24 (7/3/14) | 6 | 4 (3/1/0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 185,30 | 16 % |

| Fische | |||||||||

| Bedotia madagascariensis | Madagaskar-Ährenfisch | 144 (24/20/100) | 10 | 33 (9/6/18) | 0 | 56 | 13 | 192, 16 | 69 % |

| Cyprinodon veronicae | Charco-Azul-Wüstenkärpfling | 16 (6/10/0) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | ** | ** |

| Limia islai< | Tigerkärpfling | 49 (5/5/39) | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 49 | ** | ** |

| Parosphromenus bintan | Bintan Prachtgurami | 8 (4/4/0) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | ** | ** |

| Ptychochromis insolitus | Mangarahara-Buntbarsch | 452 (15/18/419) | 12 | 37 (8/8/21) | 10 | 222 | 0 | 192, 16 | 88 % |

| Ptychochromis loisellei | Loiselles Buntbarsch | 216 (18/18/180) | 7 | 46 (7/1/38) | 0 | 65 | 0 | 160, 16 | 72 % |

| Ptychochromis oligacanthus | Nosy-Be-Buntbarsch | 1096 (8/9/1079) | 4 | 10 (3/2/5) | 0 | 1000 | 0 | 192,16 | 63 % |

| Reptilien | |||||||||

| Cuora cyclornata | Vietnamesische Dreistreifen-Scharnierschildkröte | 1 (1/0/0) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ** | ** |

m: male, w: female, u: undetermined sex

* Status = mean value of the percentage of the target number of keepers already achieved and the target number of animals

** To be determined.

Biannual report 2 / 2019 – status update

Protecting species - Animal inventory November 1st, 2019

One year ago, when the Vienna Zoo transferred 56 specimens of the critically endangered Lake Pátzcucaro Salamander, we started with the actual implementation of the conservational breeding program Citizen Conservation. The animals were allocated to terrarium owners and zoos, in consistence with the CC philosophy that private and professional keepers should work hand in hand against species extinction.

First of their kind

Until today, five species are supervised by CC. They stand for different kinds of amphibian groups, habitats and situations of endangerment. At the reference date of November 1st 2019, 136 amphibians are in care of participating zoos, school vivaria and private terrarium owners.

More founding specimens welcome

Of all five projects more founding specimens are to be included into the program. In case of the Almanzor Fire Salamander and the Bony-Headed Toad, additional animals from Uwe Seidel and the Cologne Zoo will be included. As for the Demonic Poison Frog and the Lemur Leaf Frog, we are looking for more supplying sources in order to expand the genetic base of the CC population.

More species are waiting

A few months ago, the Cologne Zoo was first to succeed in breeding the Vietnamese Crocodile Newt Tylototriton vietnamensis. Thomas Ziegler, curator in charge, transferred some of the progeny back to the breeding station Me Linh in Vietnam. Another 12 specimen will be transferred to Citizen Conservation, in order to build a European reserve population. More species are planned to be added in 2020 – some only for real specialists, but others also for conscientious beginners and school zoos.

Animal numbers at the end of 2019

(You can scroll horizontally in the table.)

| Wiss. Name | Dt. Name | Bestand Tiere (m/w/u) | Anzahl Haltungen | Todesfälle 11/18 – 10/19 (m/w/u) | Zugänge Nachzucht 11/18 – 10/19 | Zugänge extern 11/18 – 10/19 (m/w/u) | Ziel (Tiere, Halter) | Status* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amphibien | ||||||||

| Agalychnis lemur | Lemur-Laubfrosch | 10 (0/0/10) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 10 (0/0/10) | 225, 40 | 3 % |

| Ambystoma dumerilii | Pátzcuaro-Querzahnmolch | 47 (8/5/34) | 6 | 12 (1/0/11) | 0 | 59 (9/5/45) | 225, 40 | 18 % |

| Ingerophrynus galeatus | Knochenkopfkröte | 18 (0/0/18) | 3 | 1 (0/0/1) | 0 | 18 (0/0/18) | 225, 40 | 8 % |

| Minyobates steyermarki | Tafelberg-Baumsteiger | 5 (0/0/5) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 8 (0/0/8) | 110, 20 | 4 % |

| Salamandra sal. almanzoris | Almanzor-Feuersalamander | 36 (0/0/36) | 9 | 1 (0/0/1) | 0 | 37 (0/0/37) | 185, 30 | 25 % |

m: male, w: female, u: undetermined sex

* Status = mean value of the percentage of the target number of keepers already achieved and the target number of animals

On a mission for toads – Anna Rauhaus

On the road in Cologne and Vietnam

Tropical heat, the steaming rainforest, uncounted species — while some scientists stay busy trying to catalog and describe all the amphibian species in Vietnam, their colleagues have their hands full trying to save them from extinction. Anna Rauhaus from the Cologne Zoo is one of them. With her skills as a zoo keeper, she helps her Vietnamese colleagues develop breeding spaces for endangered species, research their reproduction, and form breeding groups on site.

On a rainforest mission

The rainforests in northern Vietnam are a hotspot for biodiversity. They are home to the research and breeding station Me Linh. | Thomas Ziegler

The entrance to the “Me Linh Station for Biodiversity” in northern Vietnam. It is run by the Institute for Ecology and Biological Resources (IEBR) in Hanoi. The Cologne Zoo supports the station with staff and financing. | Thomas Ziegler

Among other things, the Me Linh Station serves as a sanctuary for confiscated or injured animals, which are nursed back to health and prepared for possible reintroduction into the wild. Monitor lizards are frequent visitors in the station. Here, they can be cared for appropriately. | Thomas Ziegler

Anna Rauhaus helps identify the sex of a stately monitor lizard at the station. The big lizards are illegally hunted for their leather and meat. | Truong Quang Nguyen

Turtles are hunted especially often because they are eaten as well as used in traditional Chinese medicine. Animals cared for at the station are marked with a transponder so researchers can recognize them if they cross paths again. | Thomas Ziegler

Several critically endangered species are bred in the Me Linh Station. The Chinese Crocodile Lizard is on the verge of extinction. Anna Rauhaus cares for the animals in the Cologne Zoo and has shared her knowledge with her colleagues in Vietnam, who have now also set up a breeding program. | Anna Rauhau

But Anna is also actively involved in research in Vietnam. Here, is recording environmental data in the habitat of the Chinese Water Dragon near the Me Linh Station. | Thomas Ziegler

Amphibians have their own space in the station. It serves as both a base for research projects and a breeding station for endangered species. | Thomas Ziegler

In addition, amphibians are kept in outdoor facilities – the climate is optimal on site. That allows researchers to collect biological data and breed animals for species conservation. | Anna Rauhaus

Just one of the many amphibian species that are being successfully bred thanks to Anna in Me Linh: the Black-Webbed Treefrog Rhacophorus kio. It is one of the flying frogs that can travel long distances between trees in gliding flight. | Thomas Ziegler

The station’s exhibits were developed in co-operation with experts from the Cologne Zoo. This co-operation helps raise awareness about the threat to local wildlife within the community. | Thomas Ziegler

Research, animal protection and breeding, training and cooperation. In Vietnam, Anna can use her diverse interests to benefit animals and nature. It's her ultimate dream job. | Thomas Ziegler

Ambassadors in Cologne

Amphibians are also being bred at home in Cologne. There they are ambassadors for their natural habitat and a key reserve for species conservation. In the past few years, Anna and her team have managed to breed nearly 20 species of frogs, toads, and salamanders, including highly endangered species, in their special breeding room for amphibians. The terrarium team in Cologne is specialized in endangered and little-researched species. They also help host and find homes for confiscated animals.

A particularly charming toad

One of Anna’s favorites is the Bony-Headed Toad. In Vietnam it is endangered, but in Cologne it is reproducing quickly thanks to dedicated care. “Bony-Headed Toads are beautiful animals with a very special charm,” Anna says. “I am glad we have been helping them multiply over several generations in the Cologne Zoo.”

From passion to profession

How do you find a job like Anna’s? “I’ve always loved amphibians. Apart from the fact that they’re just very likeable, I’m fascinated by their sheer diversity.” So much so that after a few semesters at university, Anna decided to switch to something more practical that truly inspires her: animal caretaker with a focus on species conservation. She has been a caretaker in the Cologne Zoo’s terrariums since 2014. “No two days are the same,” says Anna about her dream job. “Especially with the amphibians, you have to look at their perspective and consider how to best mimic their natural living conditions. In the Cologne Zoo, it is especially nice that the breeding is combined with research and species conservation.”

Offspring in the Cologne Zoo amphibian room

Related posts

Saving a rare specimen

Serious, not crazy

Should private citizens breed wild animals? Anyone who reads Karl-Heinz Jungfer’s story no longer asks that question. Instead, a different one springs to mind: How can we convince more people to get involved in breeding wild animals?

“Crazy about frogs.” The title of the article that caught the eye of 12-year-old Karl-Heinz in an aquarium magazine now seems prophetic. He’d already been keeping reptiles for three years, he says, but the article introduced him to a new world. In the four decades since, his life has been filled – and fulfilled – with frogs. Some people might call him obsessed, even crazy – but the biology teacher is serious about his favorite subject. He’s especially fascinated by the amazing variety of strategies frogs use to successfully reproduce.

Diversity in family planning

Karl-Heinz has intensively studied the diversity of reproduction strategies in his frogs – and has observed amazing things. The frog (Hemiphractus proboscideus) carries its eggs on its back for two months. Then they hatch into small frogs. | Karl-Heinz Jungfer

Such research findings are the product of years of hard work, made even more challenging because the frogs live in treetops and are not easy to find. Sometimes it takes years – and multiple trips – before Karl-Heinz manages to catch a second specimen. | Karl-Heinz Jungfer

The Spiny-headed tree frog (Triprion spinosus) has an amazing reproductive strategy that was only became clear through Karl-Heinz’s terrarium observations. When researchers found the first tadpoles…

… in nature, they were surprised to see eggs through their skin. They thought the tadpoles had formed these eggs and could reproduce in the larval stage, similar to the Axolotl. In reality…

… the mother feeds the tadpoles with unfertilized eggs, which Karl-Heinz discovered in his terrarium. He was even able to document the tadpoles’ begging for their food. | Karl-Heinz Jungfer

Female Spiny-headed tree frogs with their newly metamorphosed young. | Karl-Heinz Jungfer

A life dedicated to frogs

Twenty-nine years ago, on his first trip to Latin America, he found three species that had never been described by scientists. Since then, he has made frog research his hobby, and as a private scholar he has described several new species and published multiple scientific papers. And “at least once a year I need to breathe rainforest air,” he says. In 1992 he spent nine months in Brazil so that he could observe how the tree frog Osteocephalus mutabor cares for its young. Luckily for him, he also has other hobbies: like long-distance running. This ensures he has plenty of endurance for long jungle hikes.

Karl-Heinz' discoveries

By observing the frogs in the terrarium, Karl-Heinz also discovered what the Osteocephalus verruciger tree frog young look like. This is a couple before depositing their eggs… … and a freshly metamorphosed frog. By observing the frogs in the terrarium, Karl-Heinz also discovered what the Osteocephalus verruciger tree frog young look like.

In the crosshairs of gold miners

Even at home in the Swabian village Gaildorf, Karl-Heinz is surrounded by frogs. “Of course, they’re much easier to observe in a terrarium than in Amazonian treetops.” That is why he still has big plans for his terrarium room. Here, he will breed the Demonic Poison Frog for Citizen Conservation.

This small poison dart frog lives only on a single mountain plateau in Venezuela. It is extremely vulnerable, both because of the political instability in the country and because of gold deposits in the mountain. The fragile habitat of the frog is in danger of being destroyed by gold mining operations—not known for their environmental sensitivity.

Unique in evolution

That would be a tragic loss. The frog “is truly unique, the only example of its genus, and an unusual strand in the evolution of poison dart frogs,” with largely unknown reproductive habits. Karl-Heinz would like to discover the frog’s reproductive secrets—and help make it possible to raise the frog in captivity. “Citizen Conservation is the perfect chance to show that private citizens can play a role in the protection and preservation of species they care about. I want to contribute to that!”

Faced with Fungi

Faced with Fungi

A man that left as a frog lover and came back as a conservationist: Tobias Eisenberg’s story is tightly linked with one of the most dramatic biodiversity crises of our time. It is about the pure joy of fascinating animals, mysterious mass extinction, and the prospects of dedicated action.

A frog in the cradle

Tobias’ enthusiasm for frogs apparently developed very early. Family photos show him as a three-year-old, discovering frogs on walks with his family. In the 1980’s, as a teenager, he began breeding reptiles in terrariums, and he soon added amphibians: poison frogs, glass frogs, treefrogs. In part because of his fascination with frogs, he decided to study veterinary medicine. At that time, the 1990’s, he also made his first trips to Central America to observe his favorite animals in their native habitat.

Frog Biography

Tobias regularly visits the Latin American forests during vacation. While others relax, he thrashes through the jungle to photograph rare frogs. © Jörg Sens

Taking photos is more than just an exciting hobby for the ambitious amateur photographer, as his pictures have also been published in journals and books. During his excursions, Tobias also collects valuable ecological data from the amphibians’ habitat. © Nikola Pantchev

A highlight: the bizarre Sumaco Horned Tree (Hemiphractus proboscideus) frog from the Amazonas basin. The females carry their eggs on their backs until the baby frogs hatch. © Tobias Eisenberg

One of the most common and most charismatic Central American frogs is the Red-Eyed Treefrog (Agalychnis callidryas) The beautiful frogs are often kept in terrariums. They were among the first frogs that Tobias himself bred. © Tobias Eisenberg

Glass frogs also fascinate Tobias. A notable feature of this diverse group of frogs: their stomach is usually so transparent one can look inside. © Tobias Eisenberg

Tobias has made a dream come true with his new house. Right from the start, he included the technical requirements for a terrarium room and an energy-saving water supply system. Here, he breeds numerous species of frogs. © Benny Trapp, Frogs&Friends

In the midst of an extinction crisis

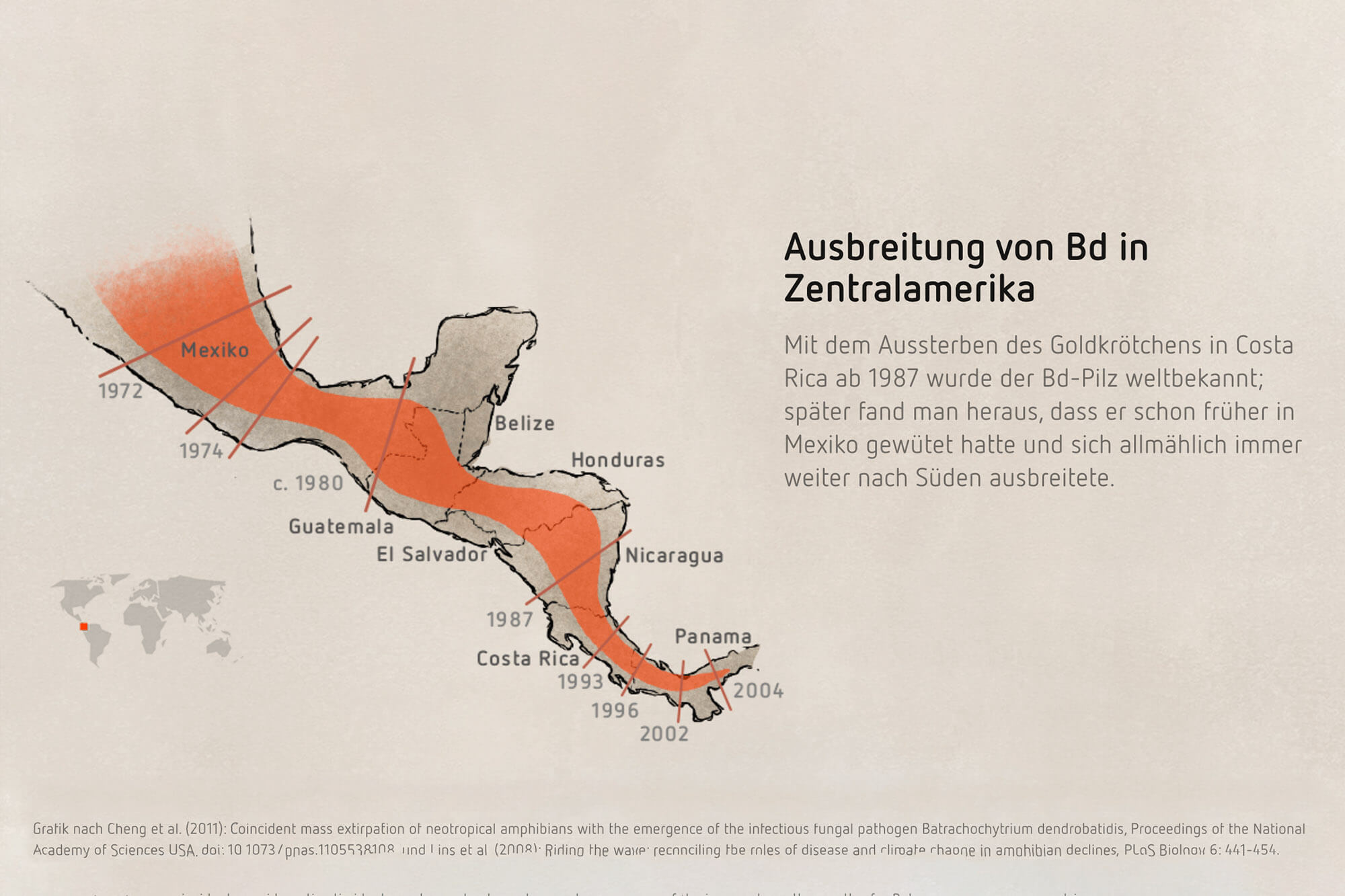

At that time, unbelievable reports started to emerge. Within a few years, frog populations and even entire species disappeared without a trace, for no comprehensible reason. Central America, Tobias’ favorite region, was particularly affected. In addition to the now famous Golden Toads and Stubfoot Toads, many leaf frog populations, Tobias’ favorite frog type, collapsed. The young veterinarian was suddenly in the middle of an extinction crisis.

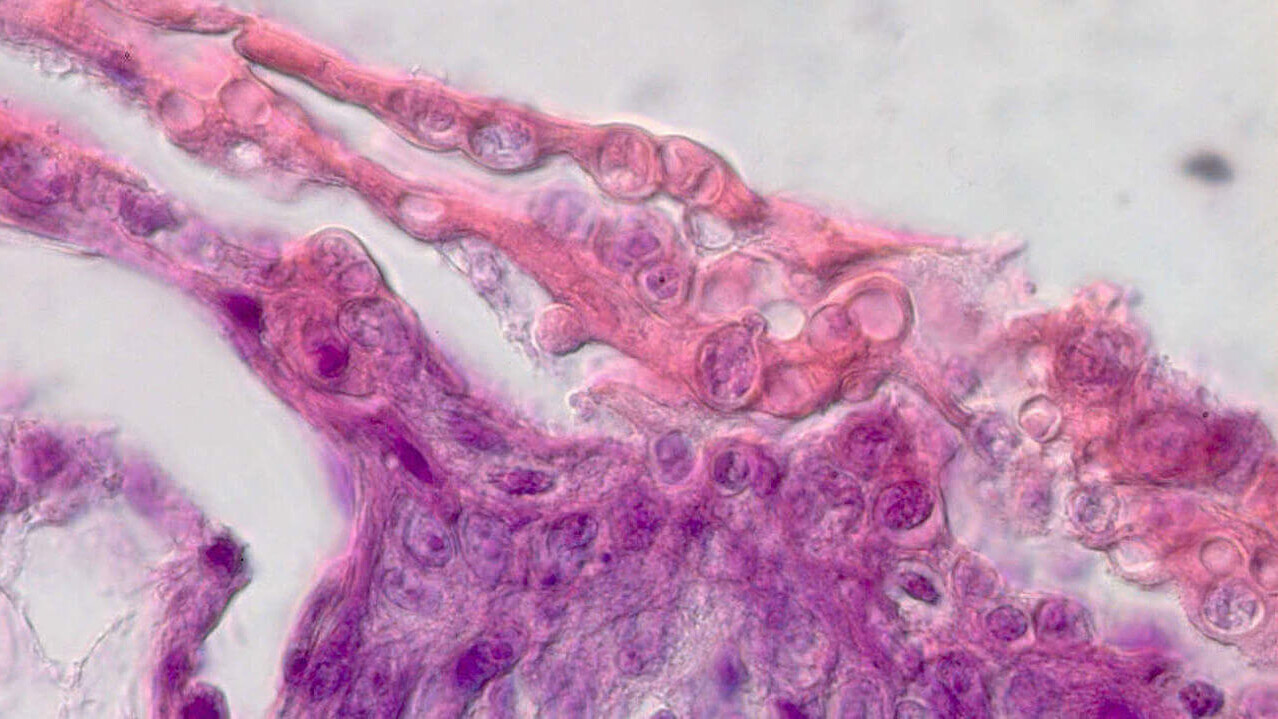

The enemy under the microscope

A cause for this mass extinction turned out to be a previously undiscovered but terrifying fungus – the Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, or Bd. The fungus has affected Tobias at work and at home. Professionally, he works in the Hessian state laboratory in Giessen and examines amphibian samples for the deadly pathogen. And privately, because his fosterlings include the Lemur Leaf Frog, which is on the verge of extinction due to the devastating effects of the fungus.

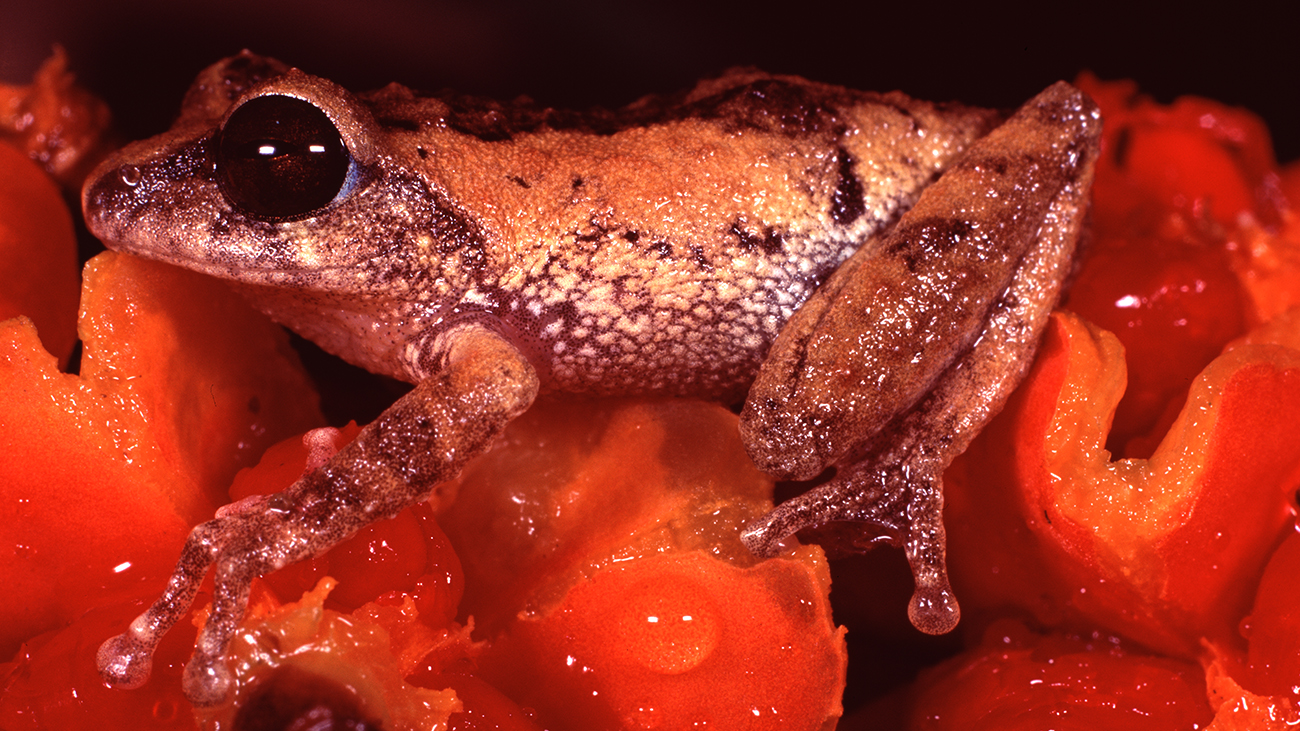

A frog close to his heart

Tobias began breeding the bright green frogs with their long, thin legs and oversized eyes nearly twenty years ago. “The Lemur Leaf Frog is a rather small tree frog,” Tobias explains. “It is one of my favorite species because of its calm lifestyle. Because of the many trips where I was able to watch it, and, of course, because of its need for protection, the Lemur Leaf Frog has a special place in my heart.”

"Because of its need for protection, the Lemur Leaf Frog has a special place in my heart."

A safe haven

So, Tobias breeds this species and hopes others will do the same. That’s why he joined Citizen Conservation: “After the different challenges captive breeding efforts have faced, I see Citizen Conservation as a smart approach. It is the first effort that tries to bring together ‘amphibian nerds’ from zoological institutions and the world of private breeders to finally start this important effort. I’m impressed!”

Systematic salamander rescue

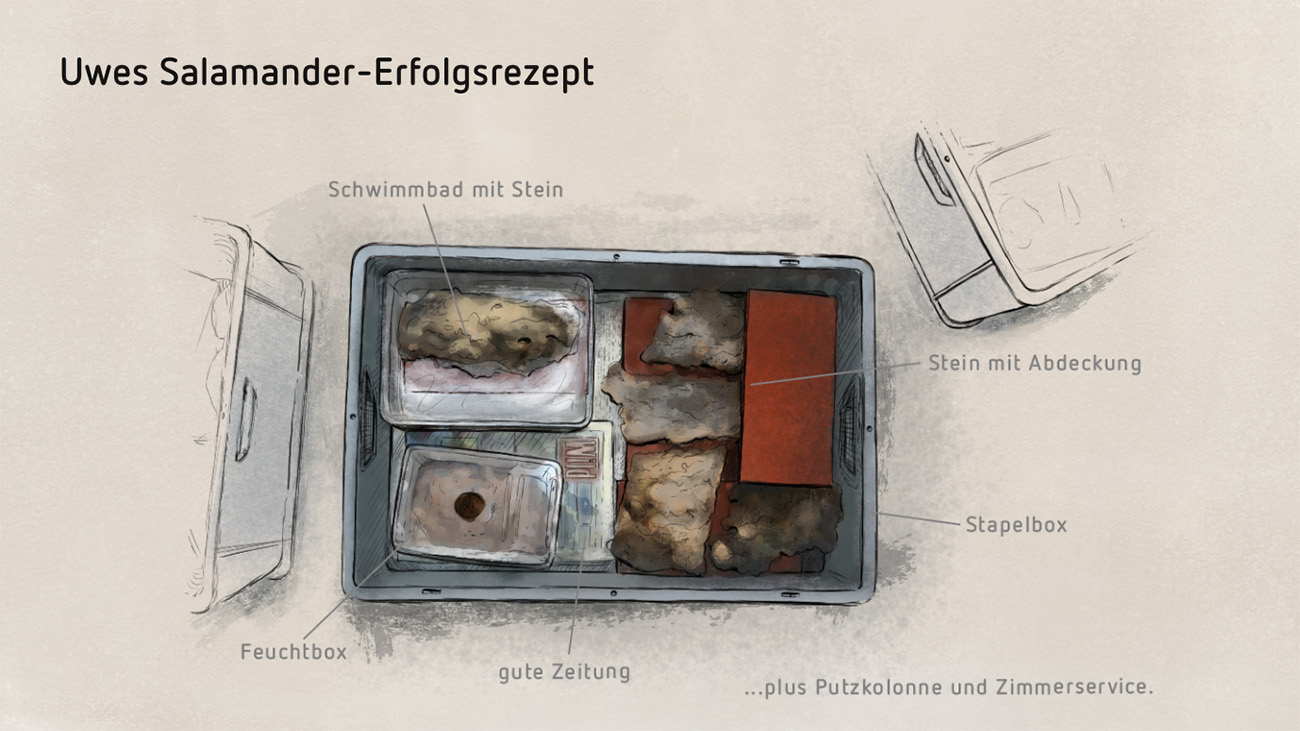

The Key Question: What matters more — aesthetics or results?

The story of the salamander breeder Uwe Seidel also tells a part of the history of modern species conservation. It begins with a fascination for the animal in its natural habitat. You want to know more—to understand the salamander’s life cycle and what this can teach us. You recreate the natural habitat in order to study the animal under controlled conditions. This works at first, but eventually you realize something is missing. Having controlled conditions means animals don’t need to worry about food or predators. They should reproduce readily, therefore. If they don’t, the conditions might not be right after all. Uwe Seidel tested this on his salamanders and came to a conclusion: what is needed, is a systematic salamander rescue.

The forested terrarium with a small stream and substrate is pretty, but less suitable for the controlled and reliable proliferation of fire salamanders. © Federico Crovetto, Shutterstock

In the end, the fire salamanders were most comfortable in gray storage boxes – at least if you count health, plentiful offspring, and a long life span as the markers of wellbeing. © Uwe Seidel

These standardized homes for salamander families are all built with the same components: newspaper substrate, hiding places under rocks and rinds, a moss-lined “moist-box,” and a pool. © Uwe Seidel

Newspaper is mainly cellulose – just like dead leaves. It is sprayed with a bit of water – fire salamanders prefer a dry environment – and replaced every other week. © Uwe Seidel

Each storage box apartment is inhabited by a breeding group of two or three animals. Thin rays of light filter in through the air vents on the side – resembling the dappled light of the forest floor. The nocturnal animals only awaken when even this light disappears. © Benny Trapp, Frogs & Friends

Fire salamanders are clean freaks

The forest terrarium presents its own dangers for the salamanders – different ones than they face in the forest. The climate fluctuates, it becomes too dry or stays too damp … In short: salamanders are stressed out trying to find a comfortable spot in such a naturally landscaped terrarium. In the end, Uwe Seidel’s love for the animals convinced him to abandon the pretty terrariums and instead turn to reliable, practical storage boxes – and the animals thank him for it with outstanding health and progeny.

Should I support this?

Your aesthetic and your ethical side may ask – is this allowed? Breeding salamanders in plastic boxes? Is this appropriate? And is it in accordance with animal welfare? There may be different opinions on this, but the fact is: the “box animals” live long and healthy lives, proliferate successfully, and their offspring grow up quickly. The layout of their mini-habitats evidently provides for the basic needs of the salamanders, “rock crevices” offer protection and a suitable microclimate, and no troublesome germs or direct sunlight disturb their wellbeing. The development of this boxed system has another advantage: for the first time, we have the capability to keep and breed salamanders in large numbers when the need arises – and that could soon be the case.

A fungus epidemic is sweeping through salamander populations

The so-called “salamander eater” Bsal (Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans) is originally from Asia and probably reached European soil years ago in The Netherlands or Belgium. Ever since, the fungus has been spreading to the south and the east. If it appears in a new habitat, almost the entire population of salamanders dies. Researchers are especially concerned about the high mortality rate: even though the fire salamander is currently not endangered as a species, the fungus could lead to the disappearance of entire regional subtypes. This is where the Citizen Conservation salamander breeders come into play. If we manage to conserve a sufficient number of the respective “geo-types” within Citizen Conservation in time, we have the option to release the original types into the wild again later. How exactly this can work in the case of Bsal epidemics is not yet clear. But one thing is clear: What’s gone is gone.